On July 31st, 1965 Donald Barthelme’s short story entitled “Game” debuted in The New Yorker. On September 29th, 2009 the first installment of Kevin Church and Ming Doyle’s The Loneliest Astronauts webcomic debuted on the internet.

They are the same thing, 44 years apart.

They both tell absurdist tales of two lunatic characters trapped in an enclosed environment. They both use satire to comment on contemporary relationships between individuals and the culture at large. They both have layers of humor and implicit tragedy.

But they are also totally different.

Allow me to explain.

If you haven’t read any Donald Barthelme, then the place to start is Sixty Stories, a collection of, you guessed it, 60 short stories by Barthelme, including “Game,” and other memorable, and brief, visions of life as we sort of know it.

(“The School” is another masterpiece in that collection, and if you head down that rabbit hole, then you need to pick up George Saunders’s The Braindead Megaphone to see his essay about Barthelme’s story structure. You could practically base a whole creative writing class around that one Barthelme story and that one Saunders essay. I know. I’ve done it.)

Barthelme was one of the great 20th century Postmodernists, and I say that as someone who is all-too-familiar with the overuse of the phrase “Postmodernism” and all of its contradictory meanings. But if you’re thinking of a writer who engages with the always-shifting truths of contemporary society with playful absurdism and still reaches profound depths, then Barthelme’s your guy.

“Game,” which has now settled into the role of token Barthelme entry in several textbooks on the development of American Literature (so that makes it as close to canonical as just about anything published in the last 40 years) tells the tale of two characters playing a strange game with one another. We soon infer that the two characters are soldiers in a bunker, holding keys to initiate a nuclear launch, but Barthelme uses a kind of naïve metaphorical language through which the narrator describes his experience, as if the unnaturally-long stay underground has driven the characters not just insane, but has regressed these grown men back to a dangerously innocent childhood.

Here’s a bit of the opening page of the story, to give you a sense of Barthelme’s oblique, and chilling (once you realize that the “bird” is actually a nuclear missile) use of language:

Shotwell and I watch the console. Shotwell and I live under the ground and watch the console. If certain events take place upon the console, we are to insert our keys in the appropriate locks and turn our keys. Shotwell has a key and I have a key. If we turn our keys simultaneously the bird flies, certain switches are activated and the bird flies. But the bird never flies.

That final line, “But the bird never flies,” is the crux of the story. The Godot which never arrives, until, maybe, the end of the tale.

My Godot reference reminds me of another bit of Barthelme. When he was once asked “why do you write the way you do?” Barthelme replied, “because Beckett already wrote the way he did.” And, to clarify the lineage of the proto-Postmodern through post-Postmodern absurdist, the simple and commonly-accepted progression is this: Beckett begat Barthelme who begat the above-mentioned-in-parenthesis Saunders.

But to that river of flowing absurdism, I would add another branch. One that trickles though Kevin Church’s Agreeable Comics internet hamlet, and runs smack into Ming Doyle‘s elegant artistry before converging back to the raging rapids of contemporary absurdist thought.

Or, I suppose I could say, “that one webcomic, The Loneliest Astronauts, is the Barthelmiest comic strip I ever did read.”

As I pointed out in the opener—the essential conflict in both The Loneliest Astronauts and “Game” are quite similar. But I also hinted that they were completely different, yet haven’t told you why.

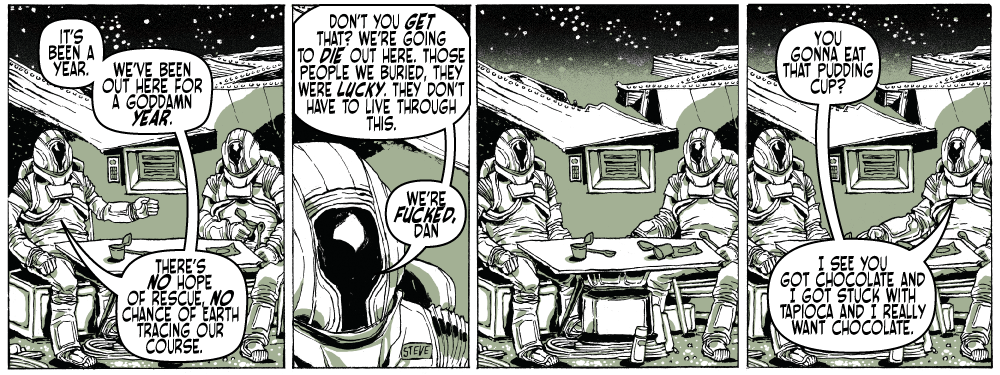

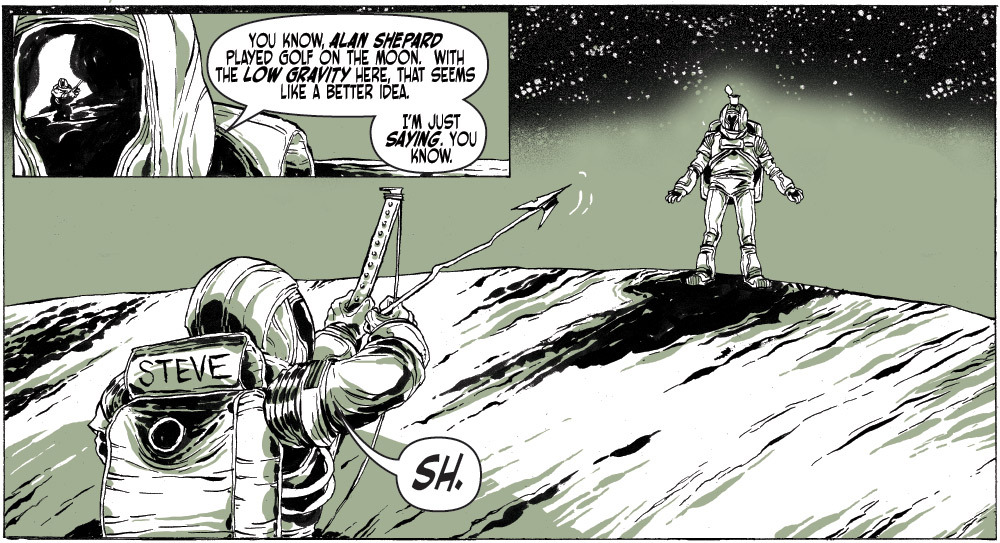

Here’s why: though both stories deal with the conflict of two guys being trapped together in an environment and going crazy in a way that makes them seem increasingly juvenile, The Loneliest Astronauts seems to have, as it’s goal, hilarity. “Game” may be hilarious at times, but its social commentary is thinly veiled.

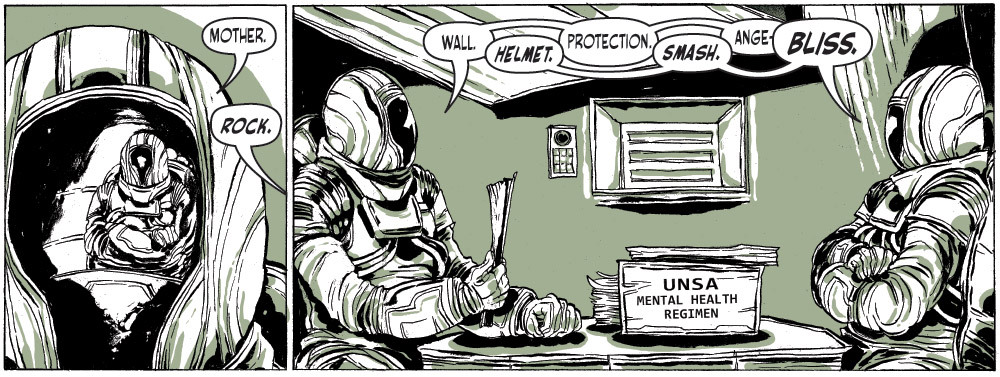

That isn’t to say that Church and Doyle’s strip doesn’t have something to say. It does. The two stuck-in-space astronauts have plenty to say to each other (or plenty of awkward silences) and their commentary on contemporary life, while physically detached from that life, is particularly telling. Yet, at its core, The Loneliest Astronauts is a gag strip that happens to have a level of intelligence about itself, even as it partakes in scatological humor and penis jokes. Would it be as true to contemporary life without such crude allusions to the plight of the man in postmodern society?

I say no.

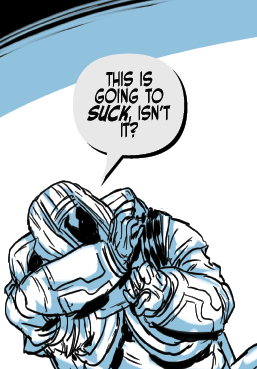

And I’ll leave astronauts Dan and Steve, as written by Kevin Church and drawn by Ming Doyle, to have the final words, with a few of my favorite (non-sequential) early installments from The Loneliest Astronauts, capturing, I think, something primal about our world today. Or maybe just making us laugh. Barthelme would be proud either way, I suspect.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. He also teaches American Literature. And comics. But mostly American Literature. Full of words.